Loading annotation data

Before jumping into building a SODA visualization, you’ll probably want to consider how you’re going to get your data loaded into the the browser in a form that SODA is happy with. On this page, we’ll cover just that.

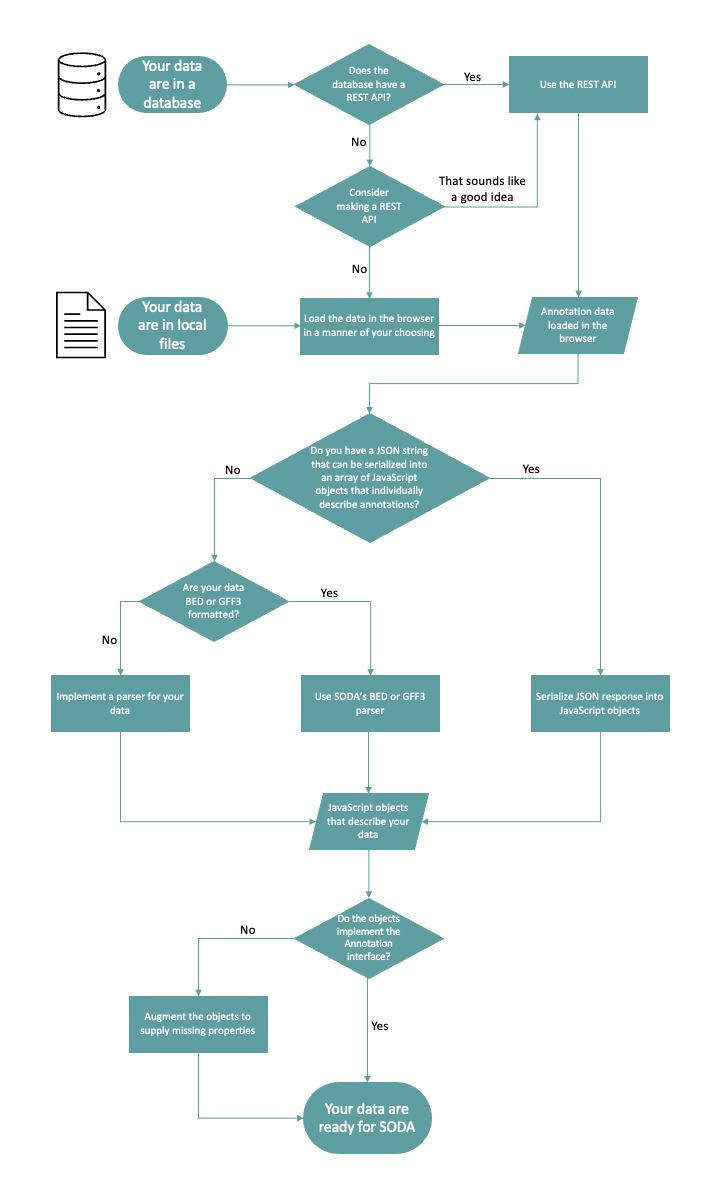

For a high-level overview of the process, you can refer to this flowchart:

Using a SODA-tailored REST API

In an ideal world for SODA, your data source would have two qualities:

The data is stored in a database with an accompanying REST API

The REST API returns JSONs that may be serialized directly into objects that implement the Annotation interface

If you can configure a database in this fashion, you can load data into a SODA visualization with very little effort.

Example SODA-tailored REST API

We host a toy database that we use to produce several of the visualizations in the Examples section.

The database has a REST API that exposes the endpoint https://sodaviz.org/data/examples/default, which returns a JSON string describing Dfam annotations:

// the response of a GET request to our toy database

[

{

"id": "dfam-nrph-1", // <- this satisfies the id property

"start": 10464, // <- this satisfies the start property

"end": 10954, // <- this satisfies the end property

"strand": "-",

"family": "TAR1",

"evalue": 1.1E-103,

"divergence": 10.26

},

{

"id": "dfam-nrph-2",

"start": 10826,

"end": 11463,

"strand": "-",

"family": "TAR1",

"evalue": 4.1E-165,

"divergence": 8.78

},

...

]

Fetch requests and object serialization

One of the easiest ways to perform a GET request in the browser is to use the JavaScript fetch API. If the response to your GET request is a JSON string, it can be automatically serialized into JavaScript objects.

For example, we might load the JSON from the above section with the following code:

// an example fetch request and subsequent JSON serialization

fetch("https://sodaviz.org/data/examples/default")

.then((response) => response.json())

.then((annotations: soda.Annotation[]) => doSomething(annotations));

// ^^ you would replace doSomething()

// with a SODA rendering API call

Defining an interface for your data

The code in the previous section will certainly produce objects that SODA can use, but it has a small problem: we haven’t told TypeScript that these objects have data properties other than id, start, and end.

If we want to make use of these properties to influence our visualization, we’ll need to write a simple interface that better describes our data:

interface DfamAnnotation extends soda.Annotation { // <- we get id, start, and

strand: string; // end for free if we

family: string; // extend soda.Annotation

evalue: number; // <- the property names and types

divergence: number; // need to match the JSON fields

}

fetch("https://sodaviz.org/data/examples/default")

.then((response) => response.json())

.then((annotations: soda.DfamAnnotation[]) => doSomething(annotations));

// ^^ now we can tell the TypeScript compiler

// that the objects we serialized are described

// by the DfamAnnotation interface

Note

If you’re using JavaScript rather than TypeScript, you don’t need to write interfaces to provide type information.

Using a standard REST API

If you’re planning to use a public database resource (e.g. UCSC, Ensembl, etc.), it’s unlikely that the REST API will be implemented in the quite the same manner described in the previous section. However, they tend to respond in a format that can be easily coerced into a format that makes SODA happy.

In this section, we’ll look at how you might load annotation data using the UCSC Genome Browser API using data from the Pfam in GENCODE track.

Format a GET request

The first step is to figure out which REST API endpoint will return the data you’re interested in.

For example, the UCSC genome browser API has an endpoint that returns annotations for a chosen annotation track, which is at the url: https://api.genome.ucsc.edu/getData/track.

Digging into the UCSC API documentation a bit, we’ll discover that this endpoint has a handful of aptly named parameters:

track- the annotation track we want data fromgenome- the genome that we want annotations forchrom- the chromosome that we want annotations forstart- the start coordinate of our query in base pairsend- the end coordinate of our query in base pairs

With this information in hand, we can craft a GET request, which might look something like:

https://api.genome.ucsc.edu/getData/track?genome=hg38;track=ucscGenePfam;chrom=chr1;start=0;end=100000

Determine the response structure

Now we need to get a sense of what the response looks like. An easy way to figure out how responses are structured is to just paste the link in your browser, which should dump the text onto your screen. You might find it useful to paste that text in a JSON formatter to make it a bit easier to digest.

The response to the above query looks like:

{

"downloadTime":"2022:08:25T19:44:29Z", // <-

"downloadTimeStamp":1661456669, // <-

"genome":"hg38", // <-

"dataTime":"2022-05-15T13:39:52", // <- you'll often find lots of

"dataTimeStamp":1652647192, // <- metadata that comes along

"trackType":"bed 12", // <- for the ride. we are just

"track":"ucscGenePfam", // <- going to ignore all of this

"start":0, // <-

"end":100000, // <-

"chrom":"chr1", // <-

"ucscGenePfam":[ // <- this is the data we are after

{

"bin":585,

"chrom":"chr1",

"chromStart":69168,

"chromEnd":69969,

"name":"7tm_4",

"score":0,

"strand":"+",

"thickStart":0,

"thickEnd":0,

"reserved":0,

"blockCount":1,

"blockSizes":"801,",

"chromStarts":"0,"

},

... // <- for the sake of brevity, we've

// removed some members of this array

],

"itemsReturned":3

}

You’ll probably notice that the data we’re interested in is stored on the ucscGenePfam property of the object.

Defining interfaces for responses

Once we’ve got the response structure figured out, we can start crafting our data-loading code, starting with a couple interfaces:

// first we'll describe the individual annotation records

interface PfamRecord {

chrom: string; // <- we'll specify only the properties we actually

chromStart: number; // <- care about. the rest of them will be there

chromEnd: number; // <- regardless, but we don't need to tell that to

score: number; // <- to the TypeScript compiler

strand: string; // <-

}

// now we can precisely describe the location and

// type of the annotation records in the response

interface UcscResponse {

ucscGenePfam: PfamRecord[]

}

Producing proper Annotation objects

Now we can serialize a response into objects, but we need a way to shape them into a form that SODA is happy to work with.

Our PfamRecord interface fails to comply with the Annotation interface in two ways:

(i) we’ve got the start and end properties, but they are named chromStart and chromEnd; and (ii) we don’t have the id property, and we don’t actually have any data that could be used for it.

Here, we’ll look at a couple strategies to fix these issues.

Using augment()

One approach is to use SODA’s augment function.

In short, augment() takes a list of any JavaScript objects and some instructions on how to transform them into objects that comply with the Annotation interface.

There’s a subtle but important nuance to using augment(): if you set the virtual flag to true on a property, the callback function will be evaluated and the value will be added as a real property on the object, but if you omit virtual or set it to false, the callback function will be added as a getter for that property.

Note

This code block starts to dip into some of TypeScripts more nuanced language features, namely intersection types and generics.

// PfamAnnotation is a type alias for the type intersection of

// the PfamRecord and soda.Annotation types

type PfamAnnotation = PfamRecord & soda.Annotation

fetch(

"https://api.genome.ucsc.edu/getData/track?genome=hg38;track=ucscGenePfam;chrom=chr1;start=0;end=100000"

)

.then((response) => response.json())

.then((response) => response.json())

.then((response: UcscResponse) => response.ucscGenePfam)

.then((records: PfamRecord[]) =>

soda.augment<PfamRecord>({ // <- augment has a generic type parameter R, and

objects: records, // it returns the type (R & soda.Annotation)

id: { fn: () => soda.generateId("pfam") }, // <- real property

start: { fn: (r) => r.chromStart, virtual: true }, // <- getter

end: { fn: (r) => r.chromEnd, virtual: true }, // <- getter

})

)

.then((annotations: PfamAnnotation[]) => doSomething(annotations));

Writing a class

If you want a bit more control over your objects, you can write a class instead. That might look something like:

class PfamAnnotation implements soda.Annotation {

id: string;

start: number;

end: number;

score: number;

strand: string;

constructor(record: PfamRecord) {

this.id = soda.generateId("pfam");

this.start = record.chromStart;

this.end = record.chromEnd;

this.score = record.score;

this.strand = record.strand;

}

}

fetch(

"https://api.genome.ucsc.edu/getData/track?genome=hg38;track=ucscGenePfam;chrom=chr1;start=0;end=100000"

)

.then((response) => response.json())

.then((response: UcscResponse) => response.ucscGenePfam)

.then((records: PfamRecord[]) => records.map((r) => new PfamAnnotation(r)))

.then((annotations: PfamAnnotation[]) => {

console.log(annotations);

chart.render({ annotations });

});

Local files

If you are interested in loading local files into SODA, you’ll need to come up with a way to load the file into the browser, then come up with a way to parse it into suitable objects. In this section we’ll give a simple example on how to accomplish that.

Setting up a webpage to accept a file input

To start off, you might add a file input tag to your page HTML:

// hypothetical index.html

<!doctype html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8">

<title>soda viz</title>

</head>

<body>

<div class="soda-chart"> // <- your visualization would live here

<input type="file" id="file-input"> // <- here's your file input

<button type="button" id="submit"> // <- here's a button we can set up to

Submit // submit the file

</button>

</body>

<script src="main.js"></script> // <- this would point to your

</html> // data loading + SODA code

Next, you might write some TypeScript that loads your data files:

// hypothetical main.js

function loadData() {

let input = <HTMLInputElement>document.getElementById("file-input")!;

let file = input.files![0];

file.text()

.then((data: string) => submitData(data)); // <- submitData() would be

} // responsible for parsing

// the file and so on

document.getElementById("submit")!

.addEventListener("click", loadData);

This gets us the file loaded into browser memory as a string. Moving on, we’ll need to decide how we’re going to process it into objects. The approach we take will, unsurprisingly, depend on how your file is formatted.

JSON files

If the file happens to be a JSON string that describes record objects, you can employ the strategies presented in the above sections concerning REST APIs. We’ll note that if your data files are products of your own tools, you might want to format your output as a SODA-tailored JSON so that you can simplify the loading process.

BED or GFF3 files

If the file is BED or GFF3 formatted, you can use SODA’s parsers to produce objects. For example, let’s say you loaded a the following BED data into the browser as a string:

chr7 127471196 127472363 Pos1 0 + 127471196 127472363 255,0,0

chr7 127472363 127473530 Pos2 0 + 127472363 127473530 255,0,0

chr7 127473530 127474697 Pos3 0 + 127473530 127474697 255,0,0

chr7 127474697 127475864 Pos4 0 + 127474697 127475864 255,0,0

chr7 127475864 127477031 Neg1 0 - 127475864 127477031 0,0,255

chr7 127477031 127478198 Neg2 0 - 127477031 127478198 0,0,255

chr7 127478198 127479365 Neg3 0 - 127478198 127479365 0,0,255

chr7 127479365 127480532 Pos5 0 + 127479365 127480532 255,0,0

chr7 127480532 127481699 Neg4 0 - 127480532 127481699 0,0,255

You can parse it into BedAnnotation objects like:

// suppose this is our submitData() function from above

function submitData(data: string) {

let annotations: soda.BedAnnotation[] = soda.parseBedRecords(data);

doSomething(annotations) // <- again, you'd probably be replacing

} // doSomething() with SODA rendering calls

Anything else

If your data are in some other format, you’re more or less left to your own devices. Unless you have something remarkably strange, the process will probably end up being quite similar to the strategies described on this page.

If you think there’s a case to be made for adding more parsers to the SODA API, we’d be interested in hearing about it.